Tarikh Nigari: Numbers Speaking through Words

Our acquaintance with Urdu literature is often limited to poetry, prose, and criticism. We seldom discern that next to these towering genres there are other linguistic art forms, too, just as appealing as others. My exploration of Urdu literature has seen me stumble upon chance inspirations. One such inspiration being Fann-e-Tarikh-Nigari, or the art of composing chronograms.

Such was the awe that I first experienced after learning about this unshaken, unusual, and unfairly untouched-upon art form, that it instantly made me relive my dread for mathematics; something which has left many a student in a cold sweat.

But what’s the occasion? Why not poetry today? What’s with numbers and chronograms? Wrestling with all these questions?

Well, today is National Mathematics Day, celebrated to commemorate the birth anniversary of India’s master-mathematician, Srinivasa Ramanujan. Now that you know that, how about learning a few things about numbers while staying in the world of words? Might as well take out that fear of numbers!

What is a Chronogram?

Simple, when words translate into numbers, the result is a chronogram!

Obviously, it’s not an exhaustive definition, but it’s good to start with. A chronogram can be best put as time-writing. Words, or a group of words, come together to yield a number, more specifically, a year in which a material event has taken place. Sometimes, these numbers even become tantamount to a Divine phrase, verse, or utterance. We’ll learn more about this in a while, but first, there is something more important.

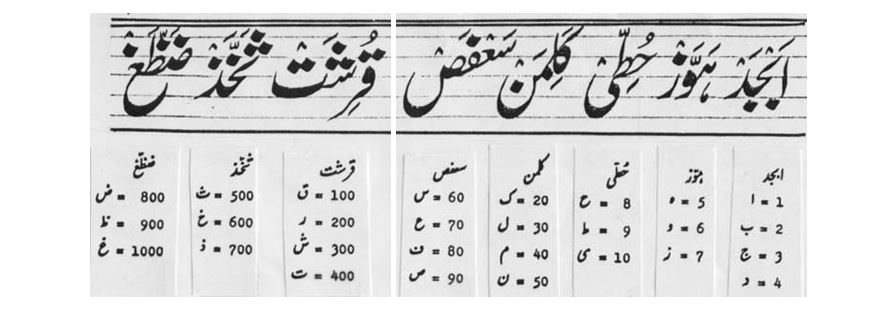

The Abjad System

Abjad is a collection of mnemonics containing all 28 letters of the Arabic alphabet system. Each of these letters is attributed a numerical value that is used in Tarikh-Nigari. The following image might help make things clearer:

As you can see, the image doesn’t include all the letters which are present in the Urdu alphabet, therefore, the remaining ones are assigned values of their closest Arabic character.

Thus, Pe equals Be, Che equals Jim, Daal equals daal, DHe equals Re, Zhe equals ze, gaaf equals kaaf, Badi Ye equals Chhoti Ye, and letters with Tashdid (double letters) are valued as a full character. Also, in Urdu, contrary to Arabic, the Hamza is valued equivalent to Alif.

Something About the Mnemonics

Usually, a mnemonic is a long stretched-out phrase abbreviated for the ease of memorizing; there is seldom any meaning in these alphabets that seem to be pointlessly stacked up against each other. But the same can’t be said about the Abjad system.

The author of Farhang-e-Asifiya, Syed Ahmad Dehlvi, quotes Risala-e-Zavabit-e-Azim and brings to light the definitions of these mnemonics in its footnote.

It reads, Abjad stands for ‘to begin’, Hawwaz ‘to find’, Hutti ‘to know’, Kalaman ‘to speak’, Sa’fas ‘to learn’, Qarashat ‘to arrange’, Sakhkhaz ‘to preserve’, and zazzagh ‘to conclude.’

The Hijri Dating System

The annual values encoded by the Abjad system are interpreted and understood in the Hijri dating system. Employing the Islamic lunar calendar, it begins with the year 622 A.D., marking Prophet Muhammad’s migration from Mecca to Medina. In short, we’ll have to convert our results from A.H. to A.D.

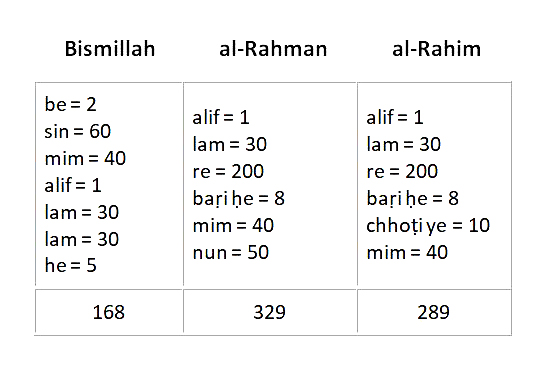

Bismillah al-Rahman al-Rahim (786)

The above phrase translates to ‘In the name of God, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful’, gives away the value 786, a number that is of marked reverence in Islam. Let us learn how it is obtained:

The three numbers tot up to 786, which is an arithmetic twin the phrase above.

Modifications in the Calculation

Like any other system, the Abjad, too, adopted new devices of calculations. Two such devices of prominence are Ta’amiya, that uses addition, and Takhrija, that uses subtraction.

In the above illustration, we’ve already learned about Ta’amiya calculation, and Takhrija can be best understood with the help of the following chronogram composed by Momin on the birth of his daughter.

Naal katne ke saath Hatif ne

Kahi Tarikh ‘Dukhtar-e-Momin’

Upon the incision of the {umblical} chord, the Angel

Pronounced the Chronogram, ‘Daughter of Momin’

The Tarikh ‘Dukhtar-e-Momin’ gives 1340, and the value for Naal (81) is to be subtracted from it -because ‘Katna’ is used for subtraction- the remaining value is 1259 A.H., which is the year 1843-44.

Historical Significance

Tarikh-Nigari has been present for centuries, and poets have been preserving important dates in verse long enough for us to know.

When Akbar conquered Gujarat, poet Abdul Rahim Khan-e-Khaanaan composed a chronogram that could be read in four languages- Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Urdu.

Dar taareekh fath-e-Kujaraat az taraf-e-Akbar Shah Hindi

Notice the word Kujarat? Till Akbar’s time the letter Gaaf had not found its place in the letter system, therefore the closest sounding letter replaced it. Interestingly, the chronogram yields the same year of victory in all of them, that is 1011 A.H., or 1602.

In 1948, when Gandhiji died, the great chronogram composer Hamid Hasan Qadiri composed a chronogram according to the Hindu calendar system, that is Bikram Samvat:

Ye aa rahi hain sadaaen bilaad-e-aalam se

Suhaag qaum ka teri chita mein jalta hai

From ‘Bilad-e-aalam’ we get 178, and from the second hemistich 1826. When added the two give Bikram 2004, that is the year 1948.

That is pretty much about Tarikh-Nigari, of course, the blog does not give away everything about it, it hopefully helps revive the long-lost interest in it. Perhaps you can compose the next one, in the comment box!

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.