Qissa-Kahani Banaam Dushyant Shakuntala

Dushyant Shakuntala: An eternal love story yet again; yet again from the Mahabharata

Dushyant and Shakuntala are the two archetypes of love. So, it appears from their story. And so it blurs the distinction between myth and reality. Shakuntala was the daughter of sage Vishwamitra and was born of Menaka, the celestial nymph. As the narrative goes, Vishwamitra who was endowed with the ability to immerse himself in deep meditation once chose to invoke his extraordinary powers of meditation. This made Indra, the King of Gods, unhappy. He feared that his overarching sway as a God might get challenged if Vishwamitra could establish the magic of his meditation rather adversely for him. To save it from happening, he appointed Menaka to distract him from his meditation. Indra’s design worked well. Vishwamitra got deeply enamoured by Menaka and fell for her. His distraction from meditation and subsequent union with Menaka led to the birth of a baby girl whom Menaka abandoned in the jungle after her birth. Since the little girl had to be taken care of, the birds of the jungle chose to surround her and look after her. This led to her naming as Shakuntala—a word derived from the Sanskrit Sakuntas which implies being surrounded by birds. Later, the kind sage Kanva took her to his ashram and brought her up. With the passage of time, Shakuntala grew up as a paragon of beauty.

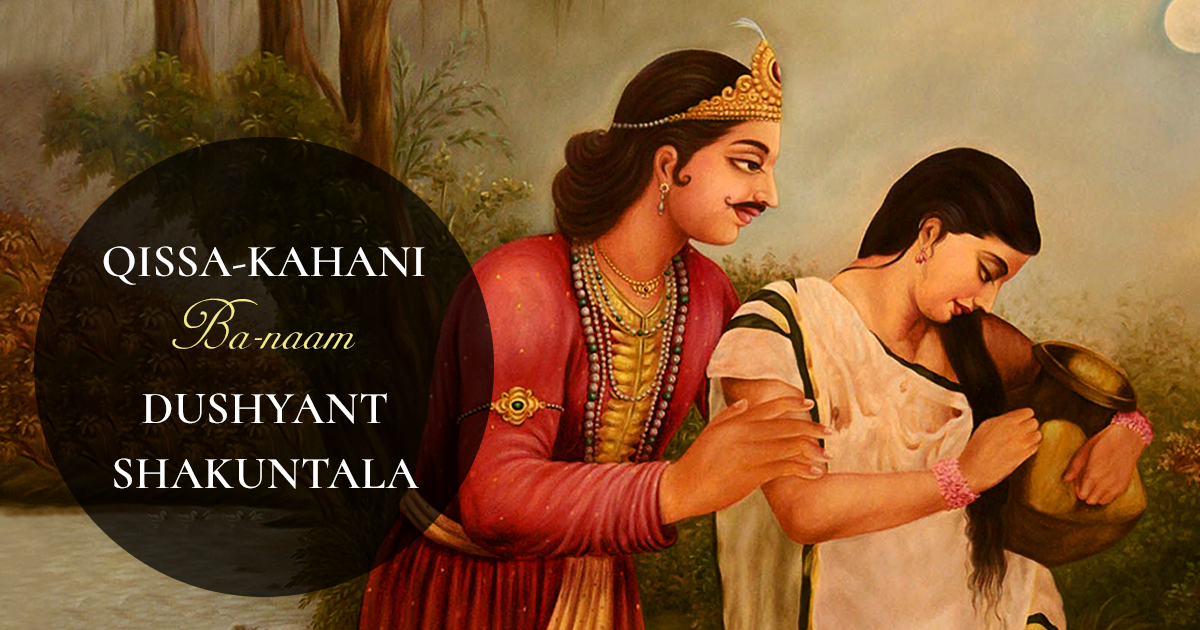

The story of how Shakuntala met Dushyant, the king of Hastinapur, is unique in its own way. Dushyant went hunting with his huge entourage in the deep jungles. He didn’t know that he would be separated from his entourage while hunting. But he actually did. Wandering around, he happened to reach the ashram of sage Kanva where he chanced to cast his eyes on Shakuntala, a beauteous being par excellence. As he saw her nursing a deer wounded by his own arrow, he felt sorry and apologised profusely to her for his act even while he could not conceal that he had already fallen under her spell. Indeed, he had come to realise what love at the first sight meant.

When Dushyant looked at Shakuntala, he could not control his patience. He proposed a Gandharva wedding with her which could be solemnised with the consent of the bride and the groom but without observing Brahminic customs and rituals. Before agreeing to his proposal, she put forward a condition that her offspring would be the heir of his kingdom. Fully swayed by her love, Dushyant accepted her condition. They tied up the nuptial knot and became husband and wife. He gave her the gift of a royal ring before leaving and promised that he would soon take her to his palace with all respect due to her.

Vishwamitra Ashram

Shakuntala kept preoccupied all through remembering her departed husband-king Dushyant. One day the sage Durwasa came to meet sage Kanva. Preoccupied with her own thoughts, Shakuntala could not care to accord a warm welcome due to him. This angered him and he cursed her saying that Dushyant would not recognise her whenever she would meet him. Later, after enough of apologies from her companions, Durwasa yielded a little and eased the curse a bit saying that Dushyant would recognise her only when she would show him the royal ring.

Shakuntala was expecting a child soon. She could not wait any longer and left to meet Dushyant. On the way, she crossed a river and the river seduced her to take a dip. As she took a dip, the ring slipped out of her finger. She was upset and felt completely helpless at this loss. She decided to move on and reach Dushyant’s court although without a ring on her finger. As Duwasa had foretold, Dushyant refused to recognise her. Pitiably enough, Shankuntala had no way to prove who she was and why she had come. She also had no option but to return to the jungle. She returned but not to the same ashram and found a new refuge for herself much deeper in the forest. After some time, it was here that she gave birth to a boy who was named Bharat, after whom the country got to be known as Bharat Varsha.

As luck would have it, a fisherman caught a fish and gave it to his wife to cook. On cutting the fish into pieces, the wife found a royal ring in the belly of the fish. Thinking that it must be from the royalty, the fisherman went to Dushyant’s court to hand it over to him. Just as King Dushyant looked at the ring, he got immediately reminded of Shakuntala. Instantly, he set out to look for her and reached the ashram in the jungle where he had met her but she was not be found there. He continued his search deeper in the forest and was struck by what he saw. There was a young boy holding the jaws of a lion apart and counting its teeth. He approached the boy in admiration and asked him his name. “Bharat,” he said, and that he was the son of King Dushyant. The appointed hour had arrived. The forgetful but the questing king had reached his destination at last. The young boy took him to his ashram where he met Shakuntala and the two got united finally. Bharat later became Dushyant’s successor whose descendants ruled successively for long.

Dushyant, Shakuntala and Bharat

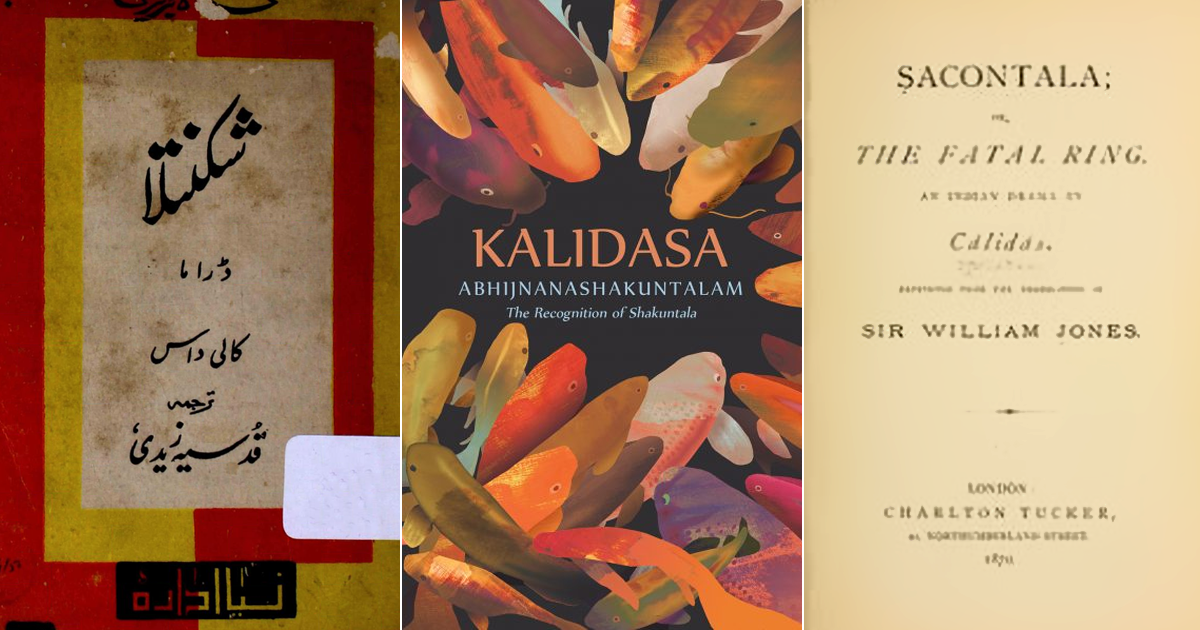

This amazing story has been a subject of multiple representations through ages in fictional, poetical, theatrical, artistic, and several other forms. It has been translated, adapted, and reworked variously in both in and outside India especially since the eighteenth century. Most of them have gone to Kalidasa who drew upon the Mahbharata to write his immortal play in Sanskrit called Abhijnanashakuntalam. This became a classic text of India and served as a prototype for numerous works in a number of languages.

It should be interesting to note how it acquired a very respectable space for itself, especially in Persian and Urdu, apart from other languages. For limitations of space, let only the names of some of those who translated or rendered Shakuntala in one way or the other be mentioned here. While in Persian there are Hadi Hasan and Ali Asghar Hikmat, in Urdu there are Kazim Ali Jawaan and Lallulal of the College of Fort William, apart from Ghulam Ahmad ibn Ghulam Haider Izzat, Akhtar Hussain Raipuri, Begum Qudsia Zaidi, Jawahar Lal, Hafiz Mohammad Abdullah, Abul Alai, Akseer Sialkoti, Nausherwan Ji Mehraban, Pandit Narayan Prasad, Ibrahim Mahshar Ambalavi, Syed Mohammad Taqi, Inayet Singh, Jugeshwar Prasad, Betaab Barelavi, Saghar Nizami, Iqbal Verma Sehar, Mohammad Farooque, Wahshat Barelavi…The list goes on. And it shows how the story of Dushyant and Shakuntala has served as a refrain in the popular discourse of the land.

If the list of those who drew upon this text in India is too long, equally long is the list of those who relived this text in various languages during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries outside India. It enamoured a big number of writers in English, French, Dutch, Danish, Italian, Latin, Polish, Swedish, Spanish, and Hungarian who rendered it in their own languages. The first-ever English translation of Kaidasa’s classic work was done by the formidable Orientalist Sir William Jones in 1789. In fact, Jones became the prototype for the West as Kalidasa became for the East. Notable among those are G. Forster, A. L. Chezy, Ott Boehtlingk, Richard Prischel, Alexi Putayata, N. Karamzin, Charles Wilkins, William Monier, A. H. Edgren, Arthur W. Ryder, Karl Burkhard, Carl Cappellar, S. Henzler many many more. The popularity of this text may best be guessed by referring to a research by Sten Konow who mentions that it has been translated in the German language at least thirty times. This gives us an idea about how this text travelled in different times and places and how it swayed the West in the past as it does even today.

Concept|Text: Anisur Rahman

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.