Dilli jo aik shehr hai

For this city of the past, the present, and the future, one name that holds centrally is Dilli.

Dilli tells its own tale

Dilli is a generic and archetypal name for a city of many fates and fortunes. It has been called variously and treated unevenly. There are many tales of power-play and politics behind each name it got during the course of its grand survival from period to period. Whatever incarnation it acquired through different periods of its history, Dilli served as a dehleez, or an entrance for many rulers—the Sultanas, the Mughals, the Marathas, and the British.

Dilli has been a seat of political power through ages; a base of literary cultures through aeons, especially since the Medieval period of Indian history. While it offered a stage for rehearsing the onslaughts of rulers, it gave its people a way with language and a hug with culture. The language it nourished came to be known as Urdu; the culture it established came to be associated with a way of life and letters.

The patterns of Dilli’s grand existence and impressive survival changed with time. With time, Dilli acquired a comprehensive identity of its own kind. As it transformed itself from age to age, so did its locational and cultural icons. Its architectural wonders–Quwat-ul-Islam and Jama Masjid–found yet other manifestations in Akshardham and Bahai temples; its Grand Trunk Road gave way to National Highways. Its older icons–Qutub Minar, Old Fort, and Red Fort–stood re-imagined as India Gate, Parliament House, and President House; its bazaars of the earlier periods got succeeded by Dilli Haat and Trade Fairs. Its Phool Walon Ki Sair manifested itself afresh into Crafts festivals; its Diwan-e-Khas got a makeover as India Habitat Centre. Some state of the art icons–Garden of Five Senses and Hauz Khas Village–stand as the modern days’ re-configured marvels of cultural transformation.

The corridors of history unfolded many miracles and misfortunes for Dilli. If Sufis and saints blessed it, plunderers tested its resilience. While Qutbuddin Bakhtiyar Kaki, Nizamuddin Aulia, Amir Khusrau, Nasiruddin Chiragh Dehlavi, Baqi Billah Shah, Mazhar Jane Janaan, Sarmad Shaeed kept its tenor, Timur Lenk, Nadir Shah, Ahmad Shah Abdali, and British rulers, tried its nerve. Loved and looted, built and re-built—again and again–Dilli spoke with remarkable understanding through its poets in all ages and on all subjects.

Poets say their own say

Ghalib, one of the greatest poets of Dilli, had seen the decline and fall of the Mughal Empire and the British rule exercising its controlling hand. He was a sore witness to the upheavals of his age, a sad and helpless observer of one culture replacing another in the wake of the cataclysmic events of 1857. He grieved on the way history was charting its course and drastically redefining lives. As Dilli was ravaged, his heart bled. He shared his anguish in his intimate letters written in Urdu to his friends as also in his diary called Dastanbuy written in Persian. Dastanbuy recorded the tragic events spread over a little more than fourteen months from May 11, 1857 to July 21, 1858. Apart from Ghalib, poets of all literary periods wrote of Dilli both with sympathy and circumspection. They wrote for themselves as they wrote for the city. They lamented, pondered, sometimes even lost hope as they philosophised upon the common destiny of Dilli and Dilliwallahs:

Mutthi bhar khaak na rahi jo gulbadanon ke khoon se surkh na huwi ho aur kisi baagh ka aik kona bhi na tha jo bebarg-o-baari ke sabab baharon ka qabristan na maloom hota ho….Aakhir dil hai, sang-o-aahan naheen, kyun na phunk jaaye aur aakhir aankh hai rakhna-o-rauzan naheen kyun na aansoo bahhaye.

–Ghalib

Dilli ke na thhe koochey auraq-e-musawwar they

Jo shakl nazar aayi tasweer nazar aayi

–Meer Taqi Meer

Pagdi apni yahaan sambhaal chalo

Aur basti nahi ye Dilli hai

–Sheikh Zuhooruddin Hatim

Ai waaye inquilaab zamaaney ke jaur se

Dilli Zafar ke haath se pal mein nikal gayi

–Bahadur Shaah Zafar

Tazkira Dilli-i-marhoom ka na chhed ai dost

na suna jaayega hum se ye fasaana hargiz

–Altaf Hussain Hali

Dilli kahaan gayein terey koochon ki raunaqein

galiyon se sar jhuka ke guzarne laga hoon main

–Jaan Nisar Akhtar

Dil mera jalwa-i aariz ne behelney na diya

Chandani chowk se zakhmi ko nikalney na diya

–Anonymous

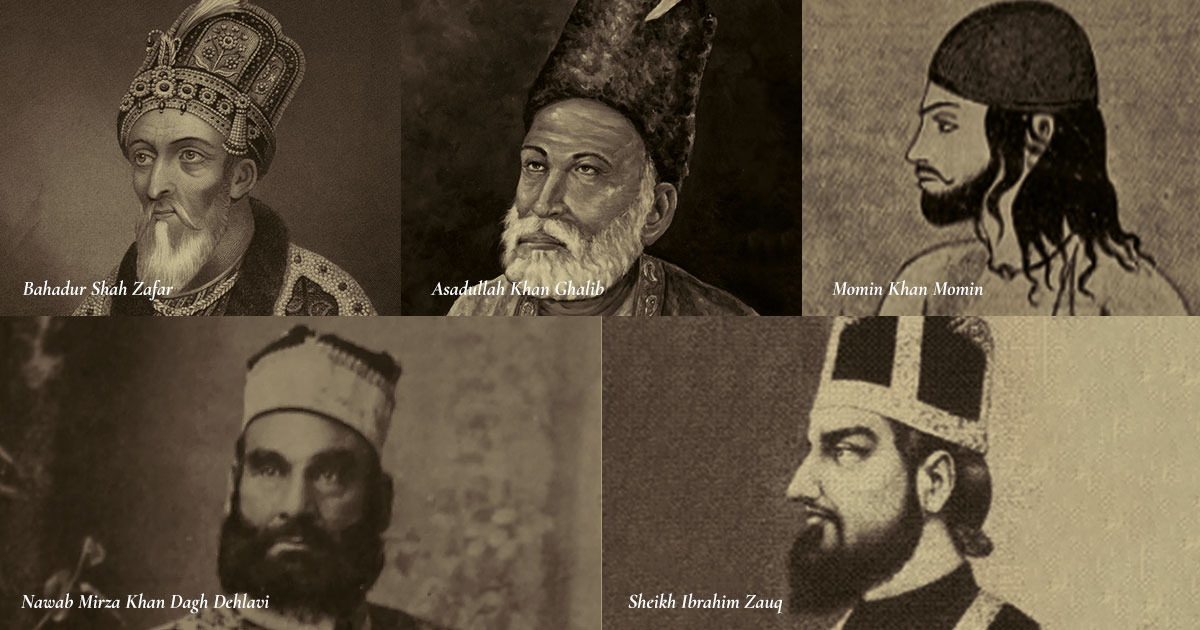

The people and the poets gave Dilli the greatest gift of the Urdu language. It was here that this language grew and got its name towards the end of the eighteenth century. It was here that it qualified as a medium of literary expression along with Lucknow, a major counterpart in creating a cultural history. As the Urdu language and literature grew remarkably well in Dilli, it boasted of its own school of poetry. The major poets of this school–Bahadur Shah Zafar, Asadullah Khan Ghalib, Momin Khan Momin, Nawab Mirza Khan Dagh Dehlavi, Sheikh Ibrahim Zauq and Mohammad Mustafa Khan Shefta—stood out as the iconic poets of the Urdu language. These poets showed remarkable imaginative vitality, evolved a direct idiom, spoke naturally, and found space in their poetry for a larger variety of experiences. Their poetry addressed issues that were plebeian and patrician on the one hand and philosophical and spiritual on the other. They spoke in a secular language shining bright with rare wit, and rich humour.

Dilli’s cultural life has had many facets. Mushaira was one of them. As the Urdu language grew with time, mushairas became a part of Dilli’s cultural life ever since the Red Fort cultivated a taste for it. Weekly mushairas were held at Madrasa Ghaziuddin, and also at the homes of the nobles at regular intervals. Mirza Farhatullah Baig’s Dilli Ki Aaakhiri Shama presents a fascinating narrative of the décore, dress codes, and mushaira manners of the day and graphically represents the literary life of the times.

Dilli speaks many lingos now

Dilli witnesses Urdu’s legacy a little differently now than before. It has developed its own forms and features. Its literary heritage stays as it improvises upon it; its cultural norms remain intact with further sheen added to it. Dilli speaks many lingos now. It is Urdu in its different forms and flavours; pure and pristine, motely and mixed with other dialects and corresponding linguistic clusters. In academic circles, Dilli speaks a language unalloyed; in corridors of power, it uses its flavour to make a point passionately. In baazaars, it turns into an argot and produces a melange of voices competing with each other. There is one language and culture in Paraathey Wali Gali, another at Kallu’s nihari joint; there is one kind of tone and tenor at Giani di Hatti, another at KFCs, PVRs, malls, and stalls. Dilli is here to live long with all its astounding variety of the chaste and the karkhandari cultures. Dilli loves and lures all; it also detracts but does not discard even if it bursts at the seams today.

Dilipur or Dhilli, Dholika or Dilli—the names given to this city once upon a time–approximate each other closely both in sense and sound. It says: in whatever way you name me, I will hold your heart and stay as a refrain in your thought and speech.

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.