Mushaira: A History of thunderous and traditional Waah-Waahs

Jo tufanon mein palte ja rahe hain

Wahi duniya badalte ja rahe hain

Those who can survive and grow in the storms

Are the ones changing the world and its norms

This couplet by Jigar Moradabadi can very well be applied to the functionality of those poetic spaces, popularly known as Mushairas, which are not just sustaining themselves amidst the strife but are also sites of literary, political and social discourse in the contemporary times.

Mushaira (mehfil or bazm) is a gathering of the poets who write, recite and listen to poetry of one another written in Urdu language, with a participative and responsive audience. It is not a contest which has a winner in the end, but the poets simply read out their self-composed poems in their patented and individual styles, crafted in accordance with a specific metrical pattern and carrying a certain loftiness of thought.

Dating its evolution, Amir Khusro in the foreword to his Ghurrat-ul-Kamaal describes a Mushaira attended by princes and other eminent personalities of the city. The Mughal king Babar in his Babarnama describes a sitting where a Persian poet was quoted during the course of the conversation who then asked his courtiers to compose poetry on the spot adhering to the same pattern. These poetic symposia came to be known as Mushairas in the 18th century before which they were called Murekhta or Majlis-e-Rekhta performed in the Rekhta language, an early form of Urdu language, literally meaning ‘scattered’ or ‘mixed’ because it contained Persian.

The onset of Indian Urdu Mushairas, called Shahi Mushairas, thus in a way began with the transitional gatherings by Mir Taqi Mir and Khwaja Mir Dard in Delhi under the reign of Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ from 1719-48. The style and craft of recitals, the well-defined and intricate decorum, the sanctity and seriousness of the language, were maintained, negligence of which was equivalent to sacrilege. Ali Jawad Zaidi in his book Tarikh-e-Mushaira wrote that Urdu Mushaa’ira had become so popular in Delhi that Lal Qila, or the Red Fort became a venue for such events. Shah Alam Sani, one of the successors to Aurangzeb Alamgir, was the first to hold an Urdu Mushaira there. The trend caught on and the courtiers and nobles followed suit. The public, too, began holding Mushairas. Sirajuddin Khan Ali Aarzoo, the anti-Persian activist, pro-Urdu revolutionary, hosted a Mushaira every month to promote Urdu.

Tarhii Mushairas were held in the courts of Oudh and Delhi. The general procedure was to send an invitation and announce at the same time a Misra-i-tarah, a half-verse to show the metre and rhyme in which the Ghazal was to be composed. When the poets had assembled, a candle was passed around. It was placed before the poet who was to recite his poem.

Much importance was attached to the order in which the poets were requested to recite, the well-known beginner coming first, those with established reputations coming later. And often, unpleasantness was caused by a poet being asked to recite too soon or before another poet whom he considered his inferior. As a result, Mushairas sometimes led to bitterness and conflict.

From 1837 onwards, when Urdu replaced Persian as the court language in upper India, it gained currency which kept this oral tradition alive. A culture was built around taking lessons in poetry writing; it even became fashionable for royalty to learn Urdu shaayari and an Ustaad-shaagird culture was accorded grave importance and reverence. Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last Mughal Emperor of India was an accomplished poet in his own right who brought alive the Mushaa’iras in his Darbar which ushered in the age of legends such as Mirza Ghalib, Momin Khan Momin and Ibrahim Zauq. From writing and then reciting the Ghazals in an uncompromising metrical pattern or tarah, to the grave mazmuun or themes of poetry which are treated condescendingly if frivolous, merge to take the shape of the literary genre of Urdu poetry which then immortalizes after its oral representation in a Mushaa’ira. The shu’aara and the saam’iin i.e. the poets and the audience together manifest the Mushairas. Dalrymple qualifies the listeners or saam’aiin as “an audience of connoisseurs” which gradually, became variegated when Mushairas started taking place in the bazaars, community centres, universities and academies, but they remained involved and engaged in the poetry just as much.

After suppressing the mutiny of 1857, the last Mughal king, Bahadur Shah Zafar was exiled to Burma and India was annexed to the British Empire in 1858. The newly founded British India found itself amidst a linguistic battle between Hindi and Urdu which sowed the seeds of Muslim Nationalism whence forth Conferences, Organizations and Societies serving Urdu under the aegis of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Altaf Hussain Hali, Shibli, Nazir Ahmad, Zakaullah, Enayatullah, Wahiuddin Salim and others, multiplied and later took the shape of All-India Muhammaden Educational Conference (1886) and All-India Muslim League (1906) and revived the cultural art form of Mushaa’iras with alterations and altercations. The gatherings became common (Avaamii) and cultural in style. “The Urdu language then developed and the Mushaa’ira became a popular feature of social life.

Mushairas became much more democratic because a literary medium had been discovered which stimulated a far larger number of people to exercise their minds in the composition and appreciation of poetry. The style of the Qasidah fell into the background, the Ghazal, with its opportunities for terse, epigrammatic expression, came to the forefront.”

Founded in 1936, the Progressive Writers Movement, anti-imperialistic and left-oriented, under the leadership of Syed Sajjad Zahir and Ahmad Ali in association with famous Urdu writers and poets like Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Hameed Ali, Saadat Hasan Manto, Kaifi Azmi, Ahmad Faraz, Firaq Gorukhpuri, Sahir Ludhianvi and several others, sought to create a climate of equality and nationalism, breathing liberation and democracy in their works. Prominent women writers like Ismat Chughtai, Amrita Pritam made it the strongest literary movement of undivided India. These groups organized Mushairas in their homes, coffee and tea houses which resonated with the “progressive” poetry recitals and played a magnificent role in creating an atmosphere of unity enriched by academic, aesthetic and creative talent.

Maqsadi Mushairas as they are called, they became purposive in nature which gave socio-political impetus to this oral literary and cultural art. Poetry and music have always played an extensively important role in forming the psychological make-up of the society. These poets and mushaa’irists not only inspired but also struck a chord with the popular masses that enabled people to form connection with their verses and performance. From Faiz Ahmed Faiz, Sahir Ludhianavi, Ahmed Nadeem, Jaan Nisar Akhtar, Habib Jalib, Amrita Pritam, Parveen Shakir and later Kaifi Azmi, Ahmed Faraz, Firaq Gorakhpuri to very recently Bashir Badr, Waseem Barelvi, Rahat Indori, Javed Akhtar, Munnawar Rana, Farhat Ehsaas, Nida Fazli et cetera continue to hold aloft the banner of purposive art and poetry.

With August 1947, came the hour of Independence but there came with it the distressing separation of not only two political parties and religions, but also two cultures and languages. Urdu and Hindi became the official languages of Pakistan and India respectively. Hindi and English became the official languages in India while Urdu became the scheduled language. But it is very deeply felt and recognized that, “Rozi roti toh beshaq di Hindi aur Angrezi ne, par jeene ke aadaab humein Urdu se aaye” (Our livelihood might depend on Hindi and English, but Urdu has taught us to be cultured) and the Mushairas then assisted in keeping the poetry and the Urdu language alive. Indo-Pak Mushairas by The Chelmsford Club in the 1950’s and 60’s revived the love for Ghazal and poetry recitals and there was a tone of nostalgia attached to it which can be felt in this couplet by Faiz:

Saba Phir Humain Puuchti Phir Rahi Hai

Chaman Ko Sajane Ke Din Aa Rahe Hain

The whizzing breeze is trying to ask

If the days to decorate the garden are here

Soon after, “the Mushaira—public yet intimate—encountered the mass media. While the Red Fort revived its historic links on behalf of the modern Indian state—hosting poets from all over the country on Republic Day—radio and television became the new vehicles for taking the legacy of the Mushaa’ira to people across the country. And over the years, many private organisations have stepped in to provide a new platform for this symbol of our syncretic culture.” Mushairas have come to serve as a cultural trope which exhibits the dynamics of the language, people, attitudes and the topical predilections.

Mushairas are unequivocally performative, but having said that, the merit of Mushaa’iras equally lies in the literariness of their content and erudition of its performers. “Urdu poetic tradition can be described in just in one word––colossal– in every respect: range, volume and music worthiness. From the 19th and into the 20th century, poetry had focused not only on “ghazalesque” themes of love and longing, but also other themes as well, the politics of mutiny, nationalism, tension between modernism and orthodoxy which consequently altered the outlook of Mushairas such that they turned propagandist in nature and socio-political in theme.”

On being asked about the changing nature of Mushairas, Munnawar Rana, an Indian Urdu poet commented in 2015, “Mushaire nahin badle, shaair badal gae, shayari badal gai” (Mushairas have not changed, poets and poetry have changed). They have always been a site of literary discussion, a platform for appreciation of poetry, a commentary on conventions and a medium of expression of multifarious themes ranging from love, longing, rebellion and reality.

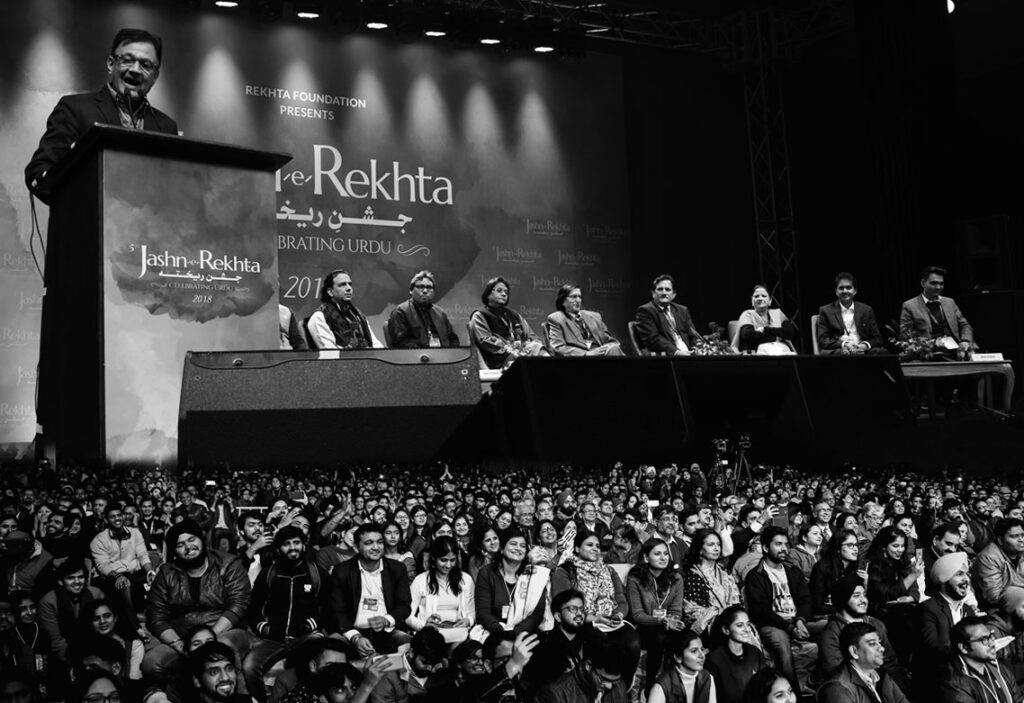

Mushairas remain a very popular cultural and secular institution specific to Urdu everywhere round the globe. It has grown from a semi-academic gathering to a cultural-commercial venture. Owing to the proliferation of Mushairas, obedience of aesthetics got limited to taking care of the seating arrangement and the hierarchy. Abdul Jamil Khan gives a detailed description of the setting of present-day Mushaa’ira in which he elucidates that “In a standard setting now, poets are seated on a dais or platform in a semi-circle facing the audience with the sadr-e-Mushaira (chairperson or master of ceremony), usually a senior poet, or high official in the centre. The chairperson’s or nazim’s introductory address which usually includes a brief description of participating poets, sets the clock in motion. Individual poets are then invited by the chair to recite, in a pecking order, the younger or not-so-famous poets preceding the well-known senior masters. The failure to follow the sequence is considered disrespectful. The line-up is thus a politically sensitive matter for the organisers and the chairperson. Poets are supposed to recite just one poem, but on demand or request, may go beyond one. Recitation is usually interactive between the poet and the audience or the other poets seated nearby. On important couplets, poets sometimes invite the listeners’ attention with phrases such as “aapki tawajjo chahiye” (your attention is needed) and “arz karta hoon” (I say that). After completion of each couplet, poets usually pause for a verbal applause, typically a “Wah Wah” (a corruption from the Persian original “bah bah” meaning “good, good”) or “bahut khoob or umda” (very good or too good), “Kya baat hai!” (What an idea!) or other similar phrases. Sometimes the poet pauses after the first misra (stanza) or a couplet to evoke a curiosity in the audience and then follows it up with the second misra, leading to loud cheers and verbal applause.” The applauding audience and the reciting poets together keep the Mushaa’iras breathing with life and culture, always reiterating the traditional art with the modern craft.

Incidentally, a Chinese poet Zhang Shi Xuan’s eloquent tribute to the power of Urdu poetry at a recent Mushaira aptly summates how the colours of antiquity can be still be seen painted at the canvas of contemporaneity:

Toot jata hai qalam, harf magar reh jata hai

Paon chalte hain magar, naqsh thehar jata hai

The pen breaks but the letters remain

the feet move on but the imprint remains

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.