Mahima Us Ki Hi Rahe Jis Ka Nao Najeer

All dignity, all majesty to him who is known as Nazeer

Drawing a portrait of one’s own self is fraught with many a risk but Nazeer Akbaradadi (1735-1830) chose to take that risk. And he took it both jovially and seriously by turns. He spoke of himself in the third person and in the past tense. He said that he was a poor teacher, timid and nervous who understood little of what all the books had in them but taught only what he understood. He also said that he did not know Arabic but knew some Persian. Also, his writing was a mix of a mature and immature hand and he knew nothing of anything except poetry which kept him happy. He had a black spot between his brows, he said, wore a headgear covering his ears, and kept mustache but did not sport beard. He added that he walked slowly, was short of height, brown in skin, and had a body proportionate to his height. He was a little sad in the old age as he was in the young age. A modest being that he was, he said that he was not capable of doing anything except teaching. At the end, he thanked God who gave him his daily morsel, howsoever humble. These read like the innocent confessions of an unpretentious being which poets are not generally. This humility is one of Nazeer’s distinguishing features.

Nazeer was unique in many respects—both as a human being and a poet. Even his birth has an interesting story to go with it. He was born after twelve siblings, none of whom could survive. This put his parents in great pain. So, when he was born, supposedly after a saintly person’s prayers and manoeuvres, a unique ritual was followed to keep him safe from evil eyes. His nose and ears were pierced and rings put into them. He was supposed to compensate for the loss of all his siblings that the parents had suffered. And Nazeer did compensate, and compensate richly.

Nazeer was born in Delhi which was then ruled by Mohammad Shah Rangeele. The city was in shambles; it had been ravaged by Nadir Shah when he was four years old and then by Ahmad Shah Abdali when he was twenty. Nazeer was taken to his nani’s home in Agra which was a safer place and where he spent all his life in all its elements. He grew up there as a man of the soil and shared his thoughts in a kind of verse that appealed instantly to both the high and the low. This put him apart from elitist poets like Meer, Sauda and Mus’hafi. He was a common man, wrote of the common people, and in the common language.

Nazeer taught the kids of Raja Vilas Rai on a salary of seventeen rupees per month. He taught other kids as well and enjoyed his time with them by being a part of the learning-living process together. He rode horses and roamed around watching people and places. Once he wanted his horse to go galloping, he whipped it. By accident, the whip touched someone passing by. Ashamed of his act, he came down and apologised. He repented what he had done albeit unwittingly. Then onwards, he never whipped a horse and allowed it to go at its own pace.

Once, he received a messenger from nawab Saadat Ali Khan of Lucknow who had brought him an invitation from the nawab to visit his court. Coming to know of his humble means, the nawab had also sent him a gift of rupees three thousand which was no less than a huge fortune then. Nazeer accepted the amount first but remained uneasy all night. When the messenger visited him the next day to get his word regarding his visit to Lucknow, Nazeer returned the money saying it had brought enough trepidation to him all night. He also politely declined the offer to visit his court.

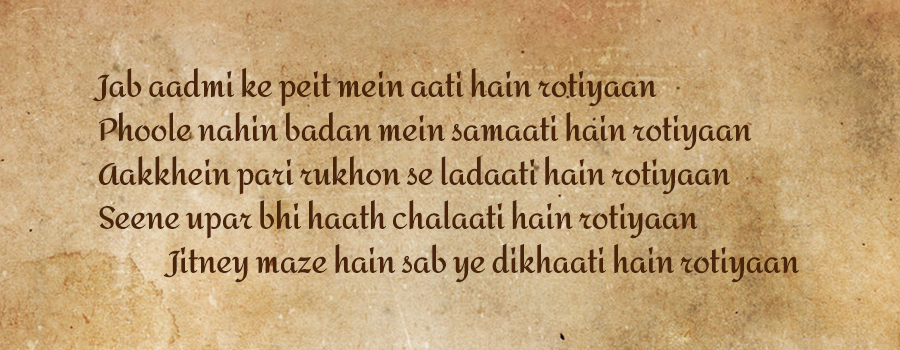

Nazeer was a poet of the masses. The masses partook of his gifts as a poet. The vendors of sweets came to him as did the fruit sellers to request for some popular verses for their products which we know now as jingles. He willingly wrote for them and turned out pieces that had their literary value too. He also wrote for the dancing girls who wished to sing his ghazals to attract more clients. Poetry was a way of life with Nazeer and he made it into something that people could delightfully live with. He wrote poems on all kinds of subjects and obliterated the distinction between the poetic and the non-poetic. He wrote on life and death, hunger and bread, seasons and rituals, poverty and prosperity, old and young age, contentment and greed, festivals and fairs, figures of romantic love and religious personages. He brought life to bear upon poetry and poetry to bear upon life. He enjoyed the freedom and the opportunity to celebrate life without any inhibition or assumption. He was deeply rooted in his flora and fauna and completely identified with his times and climes. He developed a liberal understanding of religious faiths and practices, customs and rituals, social modes and manners. Nazeer belonged to a literary school which began and ended with him.

An untutored genius, Nazeer emerged as a natural poet representing natural human aspirations in both his nazms and ghazals although his ghazals are often ignored without any critical justification. He is remarkable for his intriguing individuality and his achievement lies in how he wrote of his experiences, evolved his diction and found a form for his poetry. In spite of this, he has not been favourably considered by the critics subscribing to elitist poetics. Dwelling essentially upon a blending of Khari Boli, Braj, Awadhi, and Farsi, he formulated his counters of expression and enlivened them with conversational ease. This brought him to the centre-stage of the marketplace and gave him the identity of a poet who obliterated the distinction between the secular and the sacred as well as the grand and the plebeian. Instead of waning, his popularity has stabilised over the ages and he has survived without being ever eclipsed. In fact, he is the one who initiated a tradition of the ‘other’ in Urdu poetry which makes him uniquely relevant in today’s world of racial/communal dissensions. There is every reason for his works to be read and researched with greater seriousness now than before and every justification for his poetical compositions to be sung and dramatized before a rich complex of audiences.

Click to read the work of Nazeer Akbarabadi

Concept and text: Anisur Rahman

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.