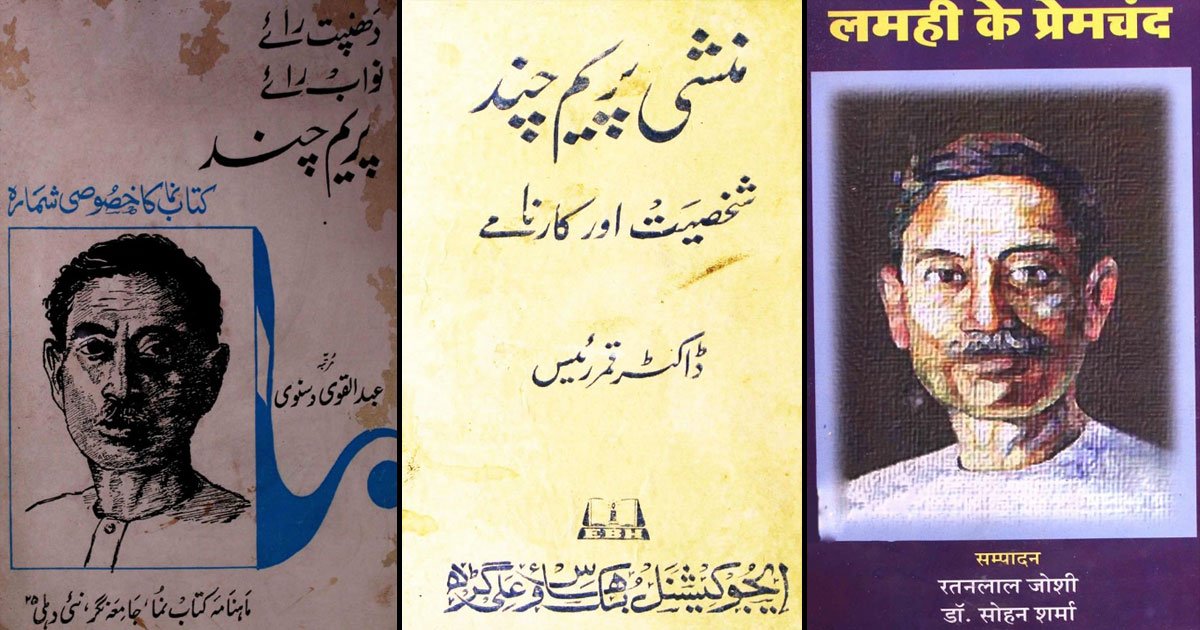

We Haven’t Served Premchand Well, Have We?

Much of what we think or say about Premchand today is usually clichéd. We have been made to believe that this literary major of our times was only a fiction writer, and a Hindi fiction writer to be precise, who emerged and stayed on primarily as a storyteller of rural life. All these are sheer misrepresentations that need to be redressed.

Let the case be put straight. First, Premchand was not a fiction writer only; he wrote extensively in various genres of non-fiction as well and extended thereby the very definition of literature. So, he needs to be considered as a rounded literary figure whose fiction bears upon his non-fiction and vice-versa. Second, he wrote essentially in Urdu but also worked hard to obliterate the distinction between Hindi and Urdu as two separate languages. As such, he was not a Hindi writer primarily but was one who later wrote in Hindi to reach out widely and also to meet his ends. Third, far from writing the story of rural life, he wrote the stories of a social order that comprised the urban and the rural together. This means that he developed a larger canvas of multiple locations where he found space for rural life as much as he did for the urban life. These submissions call for further elucidation.

Making Choices: Story and Language

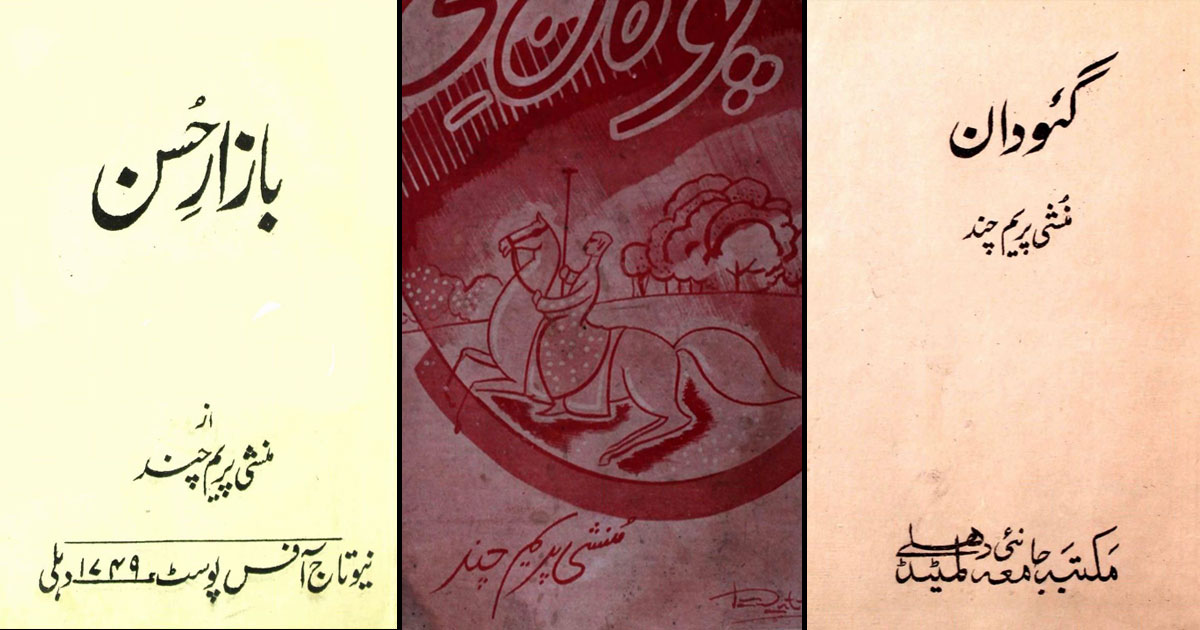

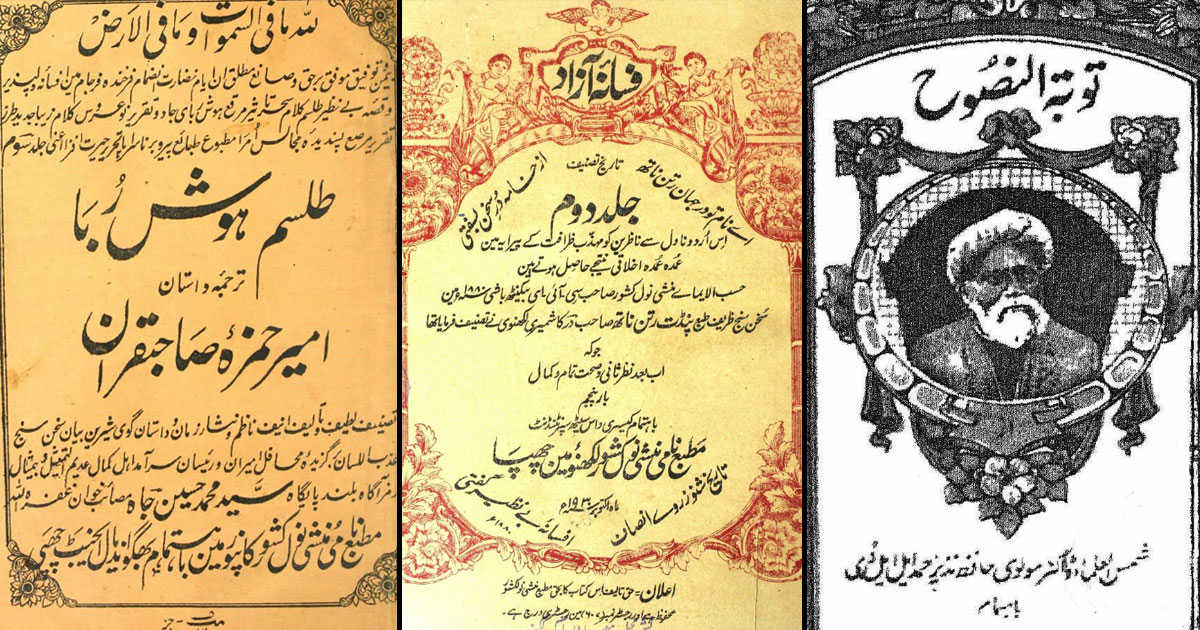

Thinking of such an innovative writer like Premchand, it should be quite possible to argue that while he extended the definition of literature, he also emerged as the first one to develop the parameters of Urdu-Hindi fiction writing. He found his stories in people, places and politics all around and they together constituted the material for his socio-literary discourse at large. Since these stories had to be told in a language, he chose Urdu only naturally in which he wrote all his life. His ability to express himself in Urdu with greater competence is well borne out by the day-to-day interactions he developed with people around, the kind of addresses he made, and the letters and miscellaneous pieces he wrote. He owed this to his initial training in Urdu and Persian and his readings of literary texts in these languages right from his formative years. He drew initially upon Tilism-e Hosh Ruba and later upon the writings of Pandit Ratan Nath Sarshar, Deputy Nazir Ahmad, and his immediate predecessor Mirza Mohammad Hadi Ruswa. His association with literary persons and editors who valued Urdu and Persian, and the general cultural ethos of the times, also contributed towards his adoption of Urdu as the language of his formal and non-formal expression. This did not keep him, however, from making a case for the coming together of Hindi and Urdu.

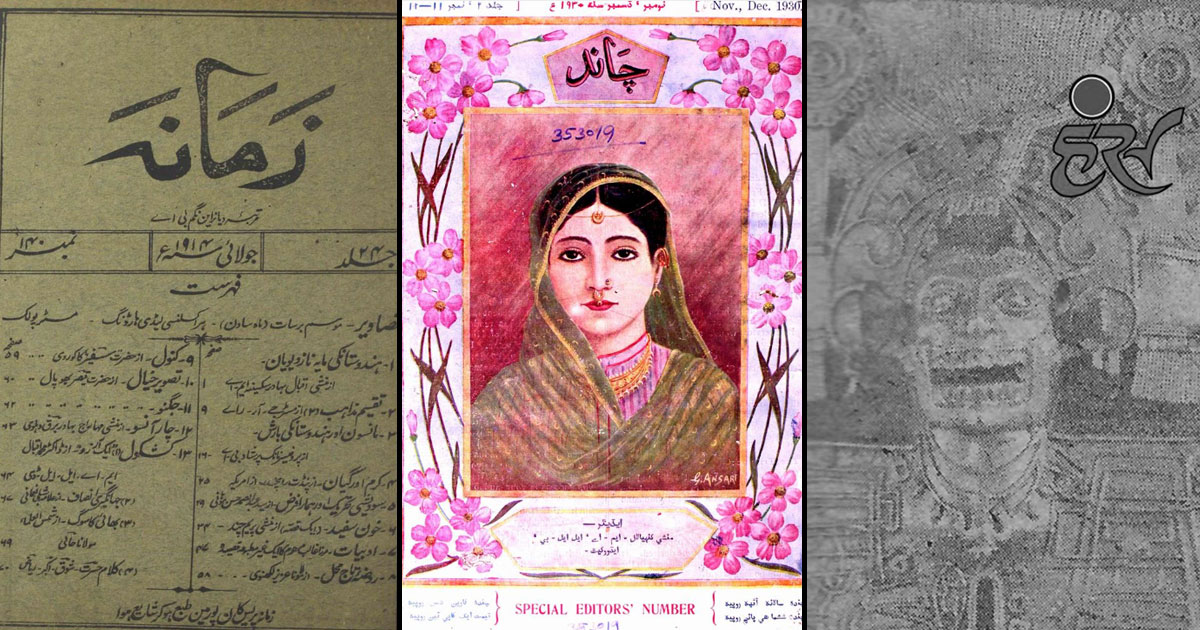

Even while Premchand wrote in Urdu, he realized that Hindi would afford him a larger readership and also a better source of sustenance which he desperately needed to explore. To put it in the right perspective, he needed both, that is a larger readership and also a safer source for his sustenance. We know that until 1916, he wrote mostly in Urdu. He chose Zamana for disseminating his views which he kept doing through a decade and more, that is from 1905 to 1920, to be precise. During 1913-15, he made a gradual shift towards Hindi. In 1915, he published in Hindi journal Sarswati and around 1918 he realized that he could profitably explore publishing in Hindi with greater seriousness. So, even while he started publishing in Hindi, he continued writing and publishing in Urdu. By 1920s, he was invited to publish in Hindi journals like Hans, Jagran, Pratap, Madhuri, Samalochak, Sarswati, and Chand in addition to Urdu journals like Zamana, Aawaz-e Khalq, Kaleem, and Asmat. In all these publications, he expressed his views on issues concerning society, culture, literature, politics, nationalist issues and imperial policies which also constituted the material for his fiction.

Points to ponder

In spite of the huge critical reception that Premchand has received from Urdu, Hindi, and English critics and translators, he has not been fully explored till this day. It is worth a thought as to why his works have not been properly preserved till date and why there is no literary archive on him worth the name so far. No Hindi or Urdu critic or researcher can tell us for sure as to how many short stories he wrote in all, nor can any source confirm the chronology of his writings and their publication dates. Similarly, no one can tell us as to which of the stories written in the two languages could be taken as the original one, nor can this be confirmed as to how and when they were anthologized. It is ironical that no one seems to know for sure as to who translated or rendered his Urdu writings into Hindi, and Hindi writings into Urdu, nor can anyone critically posit as to why he chose Muslim names for some of his stories written in Urdu and Hindu names for others written in Hindi. It must appear strange that no one can rationalize as to why his titles and texts are sometimes so dissimilar in Hindi and Urdu, nor can anyone mention as to why certain sections are dropped from or added to the Urdu version while they are present in the Hindi versions and vice-versa. Also, no one has given a wholly plausible answer as to why, after a certain date, he wrote more and more in Hindi than in Urdu, nor has anyone justified as to why he is almost always projected only as a Hindi writer. Further, there is no one to tell us how to determine his text when they are present both in Urdu and Hindi but with considerable difference, and also whether they were published first in Urdu or in Hindi and where. And finally, no one has critically explained as to why he has been only partially and infinitesimally approached so far in spite of all the attention he received over the past decades. In spite of all these gaps in Premchand scholarship, there is no denying that he developed a sustained discourse on individual and society, and tradition and modernity during the entire period of his literary career spread over twenty-nine years from 1907 to 1936.

A Case for Premchand

There is a strong case for Premchand with all his multiple identities for two reasons precisely: he evolved a language for his narratives and developed a form for them. His importance lies in how he assessed his context, constructed his narrative, evolved his diction, configured his time and place and became a torchbearer of modernism. Premchand requires retrieval; he needs to be re-discovered for the contemporary reader of Indian literature in a larger perspective. It is remarkable that there was none except him during his times, or even after, to have drawn upon the local and global conditions simultaneously. He pondered over the consequences of British rule, Russian Revolution, and World War I in his own way. He reflected upon Simon Commission and Round Table Conferences for what they signified. He critically considered personages like Hitler, Mazzini, Tolstoy, and Garibaldi. In the domain of nationalist politics, he was concerned as much with the Non-cooperation movement and Jallianawalla Bagh massacre, as he was with communal harmony and composite nationalism. He contemplated on Tilak and Gokhale, Vivekanand and Tolstoy, Bhagat Singh and Gandhi as he did on swaraj and swadeshi, shuddhi and satyagrah, capitalism and peasant activism. Passing through this meandering passage, Premchand arrived finally with a certain identity which was not that of a socialist, or a Marxist; a Gandhian, or a nationalist, but that of an iconoclast with complete faith in the organic development of a sound socio-political order. His interests were inclusive rather than exclusive; his growth was round rather than flat; his words and deeds were those of a composite intellectual who chose to interrogate, negotiate, and arrive where he wished to with complete conviction.

Concept and Text: Anisur Rahman

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.