Revisiting The Royal Recitals

Shahi Mushairon Ki Ek Tasveer

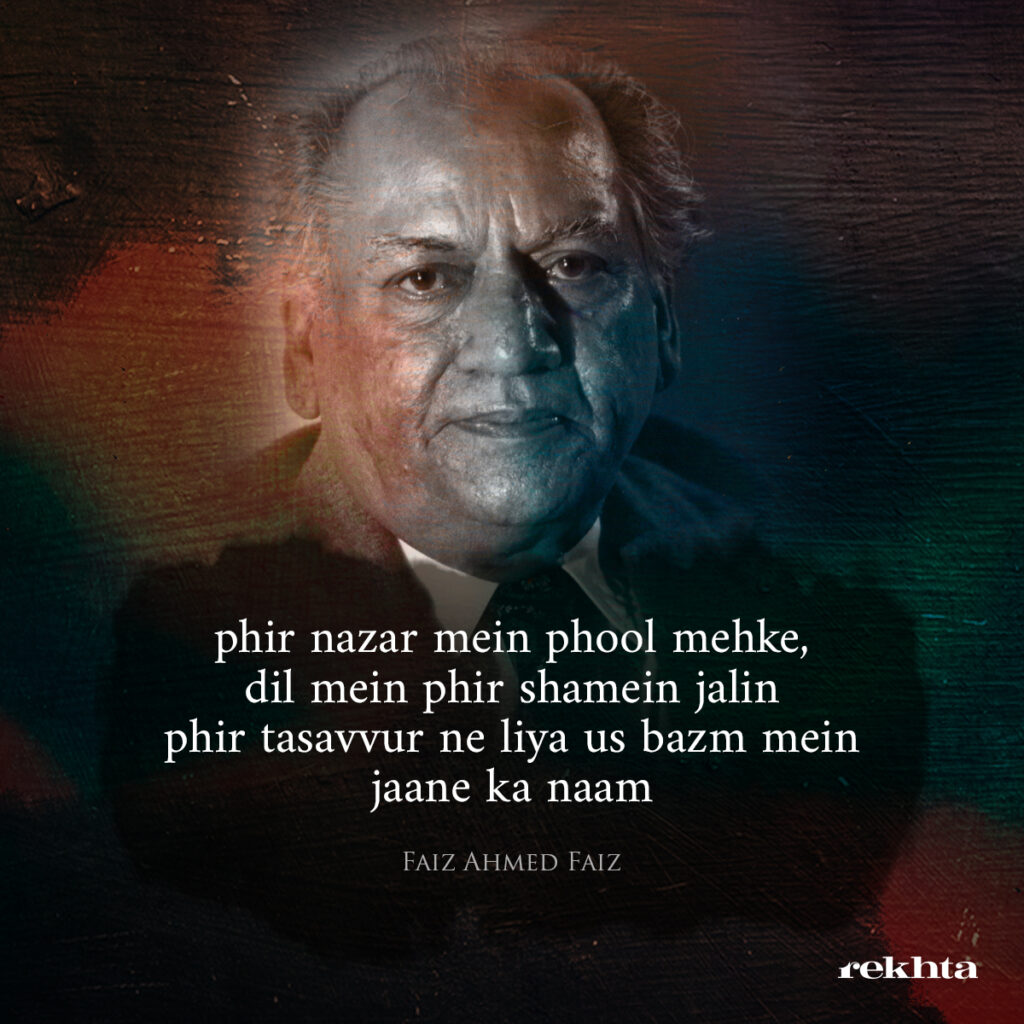

پھر نظر میں پھول مہکے دل میں پھر شمعیں جلیں

پھر تصور نے لیا اس بزم میں جانے کا نام

[Eyes aglow in the amber fragrance, candles aflame in the heart, yet again

my contemplation made me want to go to that gathering, yet again.]

The candle-lit evening, the reciprocity of Urdu verses, poems and ghazals, the profusion of lamps, lanterns and chandeliers, the fragrance of musk, amber and aloes, brightly polished and burnished huqqaas, jasmine garlands hung from the center of the roof, turned the courtyard into a veritable dome of light–– this setting might be that of a hypothetical Mushaira supposedly set in July 20, 1845, described by Farhatullah Baig of Delhi in his book, titled Delhi ki Aakhri Shama or Delhi’s Last Candle Flame, but it was based on the Shahi Mushairas that were prevalent in the Mughal Court in the 18th and 19th centuries, which have served as a prototype ever since. The couplet by the Urdu poet, Faiz Ahmed Faiz, cited above, recreates and captures the same luminous environment of the Mushaira or the Bazm a century later.

Mushairas (or mehfil or bazm) is a gathering of the poets who write, recite and listen to poetry of one another with a participative and responsive audience. It is not a contest which has a winner in the end, but the poets simply read out their self-composed poems in their patented and individual styles, crafted in accordance with a specific metrical pattern and carrying a certain loftiness of thought. Professor Ali Khan Mahmudabad traces the origin of the word Mushaira in the Arabic root word Sh-‘A-ra, which as a noun can mean ‘something that is felt’ and, as a verb ‘to feel’. In his book Poetry of Belonging published in 2020, he describes that the word Sh‘ir – meaning poem – and the word mash‘ar which signifies ‘a place where a thing is known to be’ and hence ‘a place of performance of religious services’ are derived from that Arabic root.

These Urdu poetic symposia came to be known as Mushairas in the 18th century before which they were called Murekhta or Majlis-e-Rekhta performed in the Rekhta language, an early form of Urdu language, literally meaning ‘scattered’ or ‘mixed’ because it contained Persian in it. The onset of Indian Urdu Mushairas, called Shaahi Mushairas, thus in a way began with the transitional gatherings by Mir Taqi Mir (d. 1810) and Khwaja Mir Dard (d. 1785) in Delhi under the reign of Muhammad Shah ‘Rangeela’ from 1698-1719. The style and craft of recitals, the well-defined and intricate decorum, the sanctity and seriousness of the language were ascertained, negligence of which was equivalent to sacrilege.

Ali Jawad Zaidi in his book Tarikh-e-Mushaira wrote that Urdu Mushaira had become so popular in Delhi that Lal Qila, or the Red Fort, the royal residence, became a venue for such events. Dr. Saif Mahmood, author of Beloved Delhi, in a talk ‘Dilli jo ek shehar tha’ organized virtually by Rekhta foundation during the lockdown in 2020, had fondly remarked “Lal qile ke diwaan-e-aam mein mushaire ki tarbiyat hui hai’ (Mushairas have evolved in the Hall of Audience of the Red Fort). Shah Alam Sani (d.1806), one of the successors to Aurangzeb Alamgir (d.1707), was the first to hold an Urdu Mushaira there. The trend caught on and the courtiers and nobles followed suit. The public, too, began holding Mushairas. Sirajuddin Khan Ali Aarzoo (d.1756), the anti-Persian activist, pro-Urdu revolutionary, hosted a Mushaira every month to promote Urdu.

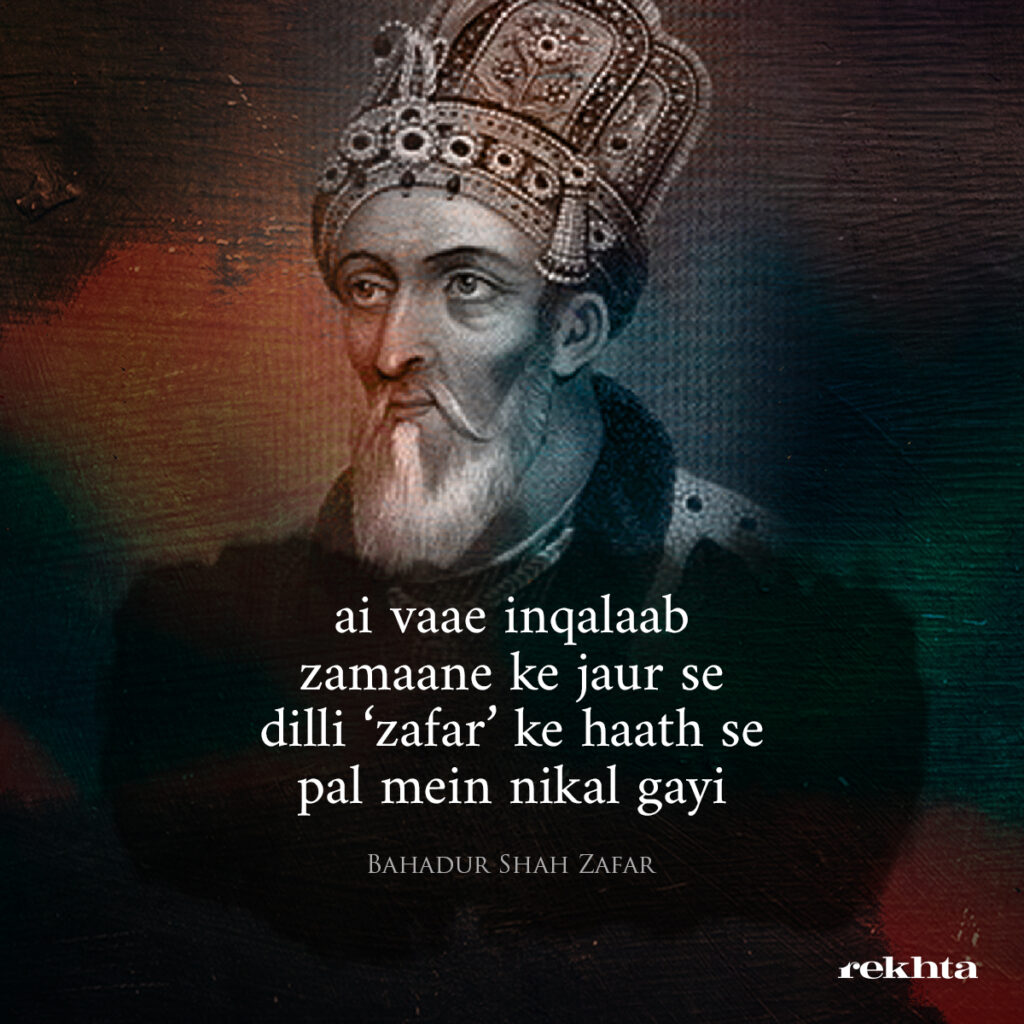

Urdu poetry or shayari as we recognize it today took its final decisive shape in the 19th century when Urdu replaced Persian in the Mughal court. A culture was built around taking lessons in poetry writing; it even became fashionable for royalty to learn Urdu shayari and an Ustaad-shagird culture was accorded grave importance and reverence. Bahadur Shah Zafar (d.1862) the last Mughal Emperor of India, was an accomplished poet in his own right, and he brought alive the Mushairas in his Darbar which ushered in the age of legends such as Mirza Ghalib (d.1869), Momin Khan Momin (d.1851) and Ibrahim Zauq (d.1854) preceded by luminaries like Mir Taqi Mir (d.1810) and Mirza Rafi Sauda (d.1781).

William Dalrymple documented in The Last Mughal, “What he (i.e.Bahadur Shah Zafar) most looked forward to was holding poetic symposia (Mushairas) in the Red Fort or in Delhi College outside Ajmeri Gate where his latest composition was read out first, followed by recitals of other poets. The Mushairas usually ended with recitals by masters like poet laureate Zauq and the greatest of them all, Mirza Asadullah Ghalib, in the early hours of the morning. As Ghalib put it, the candle burns brightest before it flickers and dies out.”

The aesthetic arrangements were given prime importance because the spirit of the verse would subsume only when recited in the enchanting setting of a Mushaira. Baig’s Dilli ki Aakhri Shama recounts Mushaira as that form of entertainment which “demands full intellectual and emotional participation within the prescribed framework of aesthetic conventions set by the masters long ago.” The account evokes the creative ambience in which the “presiding or host poet was assigned the central seat in a more or less circular seating arrangement. In front of him was placed the shama, symbol of the poetic muse.

The shama was passed on to the poet whose turn it was to present his ghazal.” Every aesthetic detail contributed in rendering the quintessence of Mushairas. “The excitement in the streets on the auspicious day, the traditional décor of the hall, the rugs and gao-takiyahs for the guests to lean against, the canopy in the bright green color, the paandaans and smell of ittr prevades the stage, the standard dresses worn by poets – jubbahs, angarkhas, choghas, kurtas, paijamahs, turbans, caps, scarfs, shoes, their hair and beard styles”, every minute attribute was treated urgent and grave.

From writing and then reciting the Ghazals in an uncompromising metrical pattern or tarah, the difficult art of tazmeen i.e. adding an extra line to their couplets so as to turn them into three-liners without losing the sense of rhythm, to the grave mazmuun or themes of poetry which are treated condescendingly if frivolous, merge to take the shape of the literary genre of Urdu poetry which then immortalizes after its oral representation in a Mushaira. Dalrymple qualifies the listeners or saamain as “an audience of connoisseurs” which gradually, became variegated when Mushairas started taking place in the bazaars, community centers, universities and academies, but they remained involved and engaged in the poetry just as much.

Shaahi Mushairas declined with the end of Shahi daur i.e. The end of Mughal Era when law and order failed in 1857. The last Mughal king, Bahadur Shah Zafar was exiled to Burma and India was annexed to the British Empire in 1858. As Zafar, a poet himself worded this defeat as:

اے وائے انقلاب زمانے کے جور سے

دلی ظفرؔ کے ہاتھ سے پل میں نکل گئی

[Rebellion & the repressive times, Sigh!

Zafar lost Dilli in the blink of an eye!]

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.