I’m over two millennia old. My tale is long; your time short. In short, I open up to you. You may pass on my tale to others.

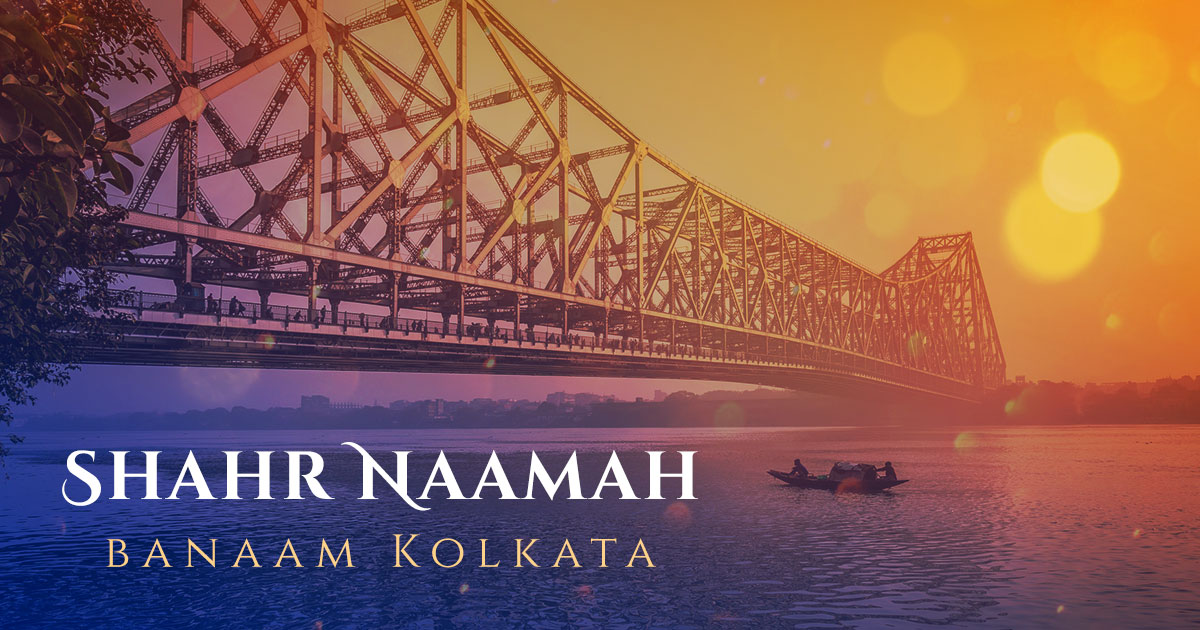

Situated on the eastern bank of river Hooghly, I have had many a name through ages. Some called me Gol Gotha, others named me Kilkila. Some believed I was Kol-ka-hata, others favoured Kalikata. Then came those who concluded I was Khal Kata, but still others chose to call me Kalkata and then Kalikota. Later, I became Calcutta; now I’m Kolkata. I have had many incarnations; each one looking at the other in the spirit of curious camaraderie. What is in a name, or appearance, after all? I’m indeed history; I’m witness. I’m over two millennia old. My tale is long; your time short. In short, I open up to you. You may pass on my tale to others.

With many a name, I’ve many a face. I’m a port; I traded in opium. I’m the Nawab of Bengal; I’m the East India Company. I’m the capital of the Raj; a face of the independence movement. I’m Bengal renaissance. I stand partitioned, bombed, starved. I am revolutionary, but stagnated too. I refuse to grow, yet I do. I choke; I breathe; I live on.

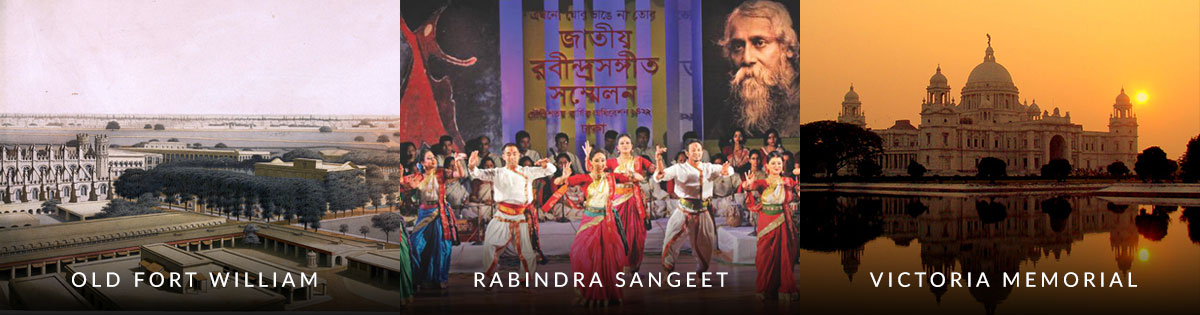

People say I am musical. No, I’m music incarnate. I’m Rabindra Sangeet. I reside in the hearts of my poets; I’m poetry. I write plays; I’m a play myself. I’m a teller of tales; I’m a tale in me. Every day is my Poila Boishakh; my new year. I rise each year as goddess Durga; sing carols in streets on Christmas; spread out on roads on Eid. I wear sari; salwar-kameez too; I dress up in suits; in dhoti kurta too. I speak Bangla, Urdu, Hindi; Odia, Punjabi, Chinese too. I am multilingual.

I spread out the finest cuisine on my platter; I offer roshogolla to sweeten your teeth, mishti doi to taste your tongue, sondesh to cure you of illness. I’ve birayani for you to savour, shahi tukda to relish. I feed the hungry belly in nooks and crannies with rice and lentil. I’m alive in five star hotels, addas, paras. I’m idiosyncratic. I’m the city of joy.

I live in Victoria Memorial; I sleep in the museum close by. I bear Indo-Islamic, Indo-Saracenic, imperial motifs but I am not funny. I’m spread on the racks of Asiatic society; I’m there at the stacks of National Library. I’m Fort William; a Black Hole too. I drink in Ghalib Bar; suffocate in Chandni Chowk. I dance on Howrah Bridge; dine in China Town. I play smart in Park Street; go grey in Park Circus. I bow down in Tipu Sultan Mosque, pray at Kali Temple, make confessions at St. Paul’s Cathedral. I’m the praying kind. I play in the Eden Garden every season; I’m the sporting type.

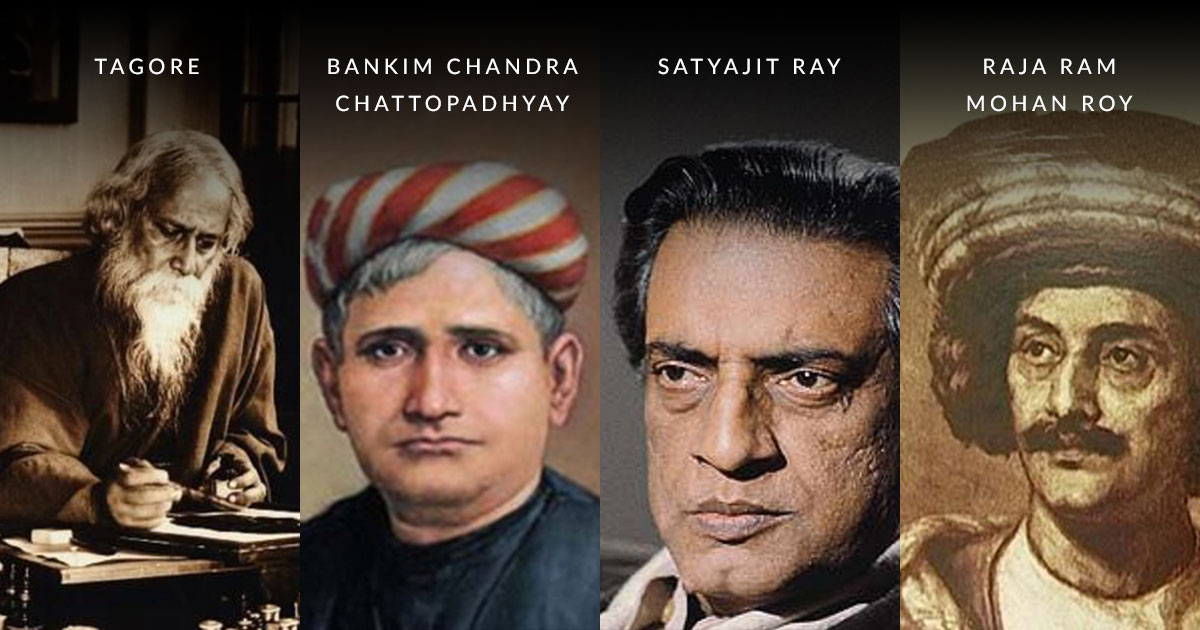

My tale is told in many ways. Bankim, Tagore tell in one way; Ram Mohan, Vivekananda in another. Satyajit, Ritwik choose one mode; Kallol, Hugryalist another. I get written in little magazines; I find myself reported in newspapers. I am writ large on the city wall. I am too legible, too audible. I’m the people; I’m the politics. I’m too prone to anger; too easy to calm down; I’m pure. I enjoy my glory and survive in misery. I’m Kali in many of her manifestations as time, doom, sexuality, and strong mother.

My poets have glorified me in all times. Urdu poets and writers have loved me for my variety as matter, motif, graffiti. Raza Ali Wahshat, who appended my name to his in sheer love for me, was my pride. Perwez Shahidi, Zafar Uganawi, Qaiser Shamim, Alqama Shibli, Hurmat-ul-Ikram are my treasured ones. Aabshar, Akhbar-e-Mashriq, Ghazi, Akkas, Rashtriya Sahara report me in their columns. My great institution Madrasa Aliah is historic in nature; it has now appeared in its new avatar as Aliah University.

My state has had the luck of hosting great Sufis and writer — Hazrat Ashraf Jehangir Samnani and Hazrat Sharfuddin Yahya Maneri. My poet Qazi Mohammad Sadiq Akhtar made me proud when Ghaziuddin Haider, the ruler of Awadh, chose him over the poets of Lucknow and Delhi to make him the poet laureate. I feel valued, venerated.

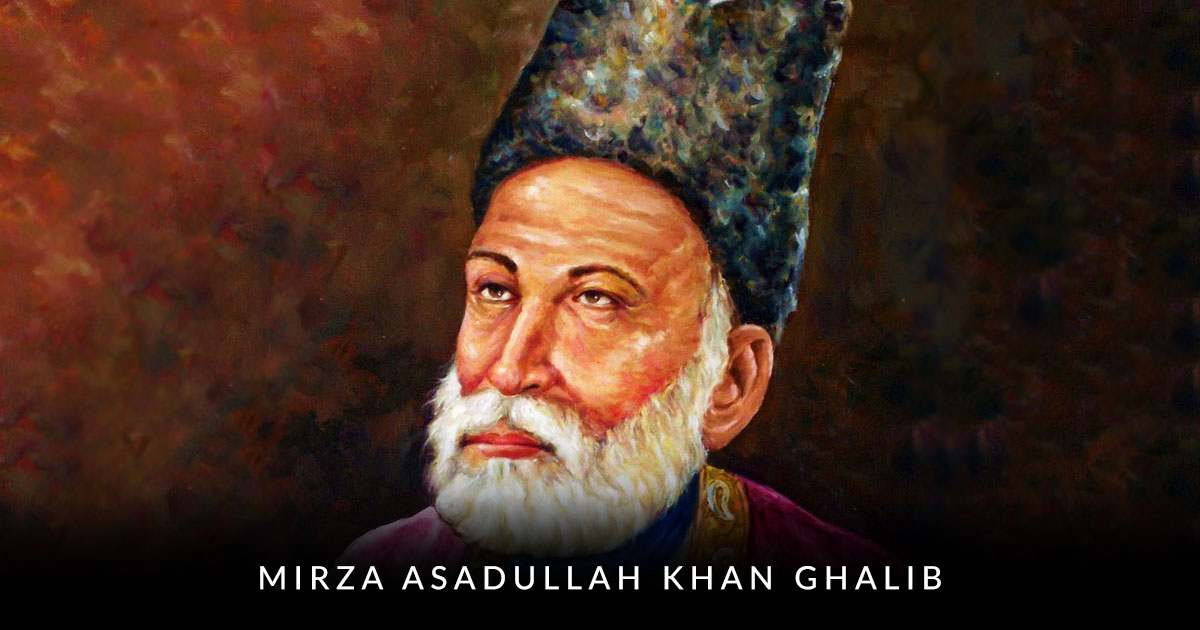

I was happy hosting Ghalib. He travelled all the way from Delhi to reach me. About the travails of his arduous journey he said, “Triumphant we reached Kalkatta and washed away the scar of distance from loved ones with wine.” Kind to me, he said that my people could see a hundred years behind and a hundred years ahead. He mentioned my places Simla Bazar, Gol Talab, and Chitpur Bazar in his letters. He praised me and my people, my places and my wine, my greenery, and of course, my mangoes. He paid me a rent of six and ten rupees at two residences. He participated in a mushaira at Calcutta Madrasa attended by around five thousand poetry lovers and recited two of his Persian ghazals. I saw someone from the audience fiercely finding fault with him and shouting. Ghalib did not take it lying low, sent a rejoinder, and initiated a controversy. For what this honoured guest of mine was, he wrote an apology called Baad-e-Mukhalif but not without a ring of sarcasm in it. I also saw him making friends with Maulvi Sirajuddin who edited Aaeena-i-Sikandar. Ghalib followed his advice and put together his first collection called Gul-e-Rana of four hundred fifty Urdu and an equal number of sher in Persian. Even after leaving me unwillingly for good, he kept me close to his heart and wrote once, “One should be grateful that there exists such a city. Where in the world is there a city so refreshing?” He pined for me all his life even after he departed with a heavy heart: Kalkatte ka jo zikr kia tum ne humnasheen/ Ek teer mere seene mein mara ke hai hai

I am so proud of Abdul Ghafoor Nassakh and Ali Raza Wahshat Kalkattavi. I brought Wahshat to my famous Madrasa Aliah. I gave him a mentor for his poetry in Abul Qasim Mohammad Shams Kalkattavi, son of Abdul Ghaffar Nassakh, who was himself a poet. Wahshat taught at Islamia College which has grown into Maulana Azad College, and later at Lady Brabourne College. He created an atmosphere that was congenial for poets and writers. He held mushairas and invited poets from far and wide. After he saw some riot-torn days, this dear poet of mine chose to settle in Dhaka but he remains mine still. I wonder if he wrote this for me: Aur ishrat ki tamanna kya karein/saamne tu ho tujhe dekha karein. Even Dagh had his own way of saying his say about me: Koyi chheetein padein to Dagh Kalkattey nikal jaaein/Azimaabad mein hum muntazir saawan ke baiththe hain.

One of my postmodernist Urdu poets, Ain Rasheed, wrote almost a dirge for me. Rasheed’s dirge, in fact, indirectly shows his deep love for me. He configured me in his poem “City” thus:

With your dirty feet spread out.

The ants creeping on your chest

Stare at the sun.

When half a dozen foreign physicians

Announced unanimously–

‘The disease is terminal; it will kill soon’–

You only looked at them

Like a shriek-stricken child

And sank into silence.

Dirty! Wicked! Cruel!

City, people say you are wicked

And I’ve seen myself–

At dusk, your decked up, painted women

Gulp the tottering young men.

Cruel!

When at late nights your intellectuals in rickshaws

Go to commit suicide

You remain silent.

City, I’m sick of your wild desires

City, when would you take off your dirty clothes?

City, people say buttons will be made of my bones when I die

City, what scripts are these on your walls?

City, I haven’t read a newspaper for months

City, you have forgotten to add sugar to your tea;

It tastes like tears

City, I feel sleepy,

Tend me to sleep.

Translation: Anisur Rahman

Ain Rasheed’s city is non-else but me. I am awake; wide awake. I wish to live long with all my odds and evens. I am what I am.

NEWSLETTER

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.